On August 30, OCSCD’s Education Outreach Coordinator, Becky Laboy and Conservation Specialist, Kristin Adams, gathered with fellow members of the New Jersey Bay Islands Initiative (NJBII) at the Long Beach Township Marine Field Station for NJBII’s 2nd annual field trip. This year’s educational excursion focused on the erosion occurring at Clam Cove Island, which lies adjacent to the Field Station and is jointly owned by Long Beach Township and Ocean County. Clam Cove is representative of all bay islands in that it provides protection to residents living on the barrier island, as well as the mainland. It absorbs wave energy and flood waters, and provides habitat for myriad wildlife, from hermit crabs to diamondback terrapins, to endangered yellow-crowned night herons. Like all NJ bay islands, its existence is under threat due to severe erosion occurring along its edges.

Angela Andersen, Field Station Manager for the LBT Marine Field Station, works with Dr. Tom Herrington, Associate Director of the Urban Coast Institute at Monmouth University and Kimberly McKenna, Interim Executive Director of the Coastal Research Center (CRC) at Stockton University, and their respective students, on a federal grant that focuses on the assessment and restoration of 5 bay islands within Long Beach Township. Ms. Andersen engages in preliminary island assessment with the Coastal Research Center and preliminary restoration design with Monmouth University. Clam Cove Reserve is the #1 focus area of the 5 islands.

What is causing the erosion?

Dr. Herrington, Ms. McKenna and their undergraduate and graduate students are working to analyze the erosive forces that are affecting bay islands throughout our coastal region. Dr. Herrington’s students, Tyler Barkey, Nicole Cappolina, and Alexis Baumgartner have measured tides and currents around Clam Cove Island to determine the natural movement of sediment onto and off of the island, in order to understand why the island is changing and to aid future restoration efforts.

There are sediment and grain size differences on the northern and western sides of Clam Clove Island that indicate how the system is changing. A large amount of sand is coming into the system and depositing along the northern sides of the island. It is determined that the sand is migrating in from beach replenishment on Long Beach Island, through the Little Egg Harbor Inlet and settling in sandbars to the north of the island. It then migrates downward to Clam Cove Island creating new marsh. This is a good news!

Tyler Barkey analyzed the wave action effecting Clam Cove Island and created a model to predict future waves. Using wind speed, duration, and the distance the wind can travel over open water, he was able to calculate wave height and period using the Sverdrup-Munk-Bretschneider (SMB) formula. He noted that even small waves can have a big impact on erosion of marsh edges. Wave action, intensified by recreational boater activity, storms and sea level rise all contribute to the degradation of important natural island structures.

The western edge of Clam Cove Island is taking a chronic beating due to these erosive forces. This is not good news!

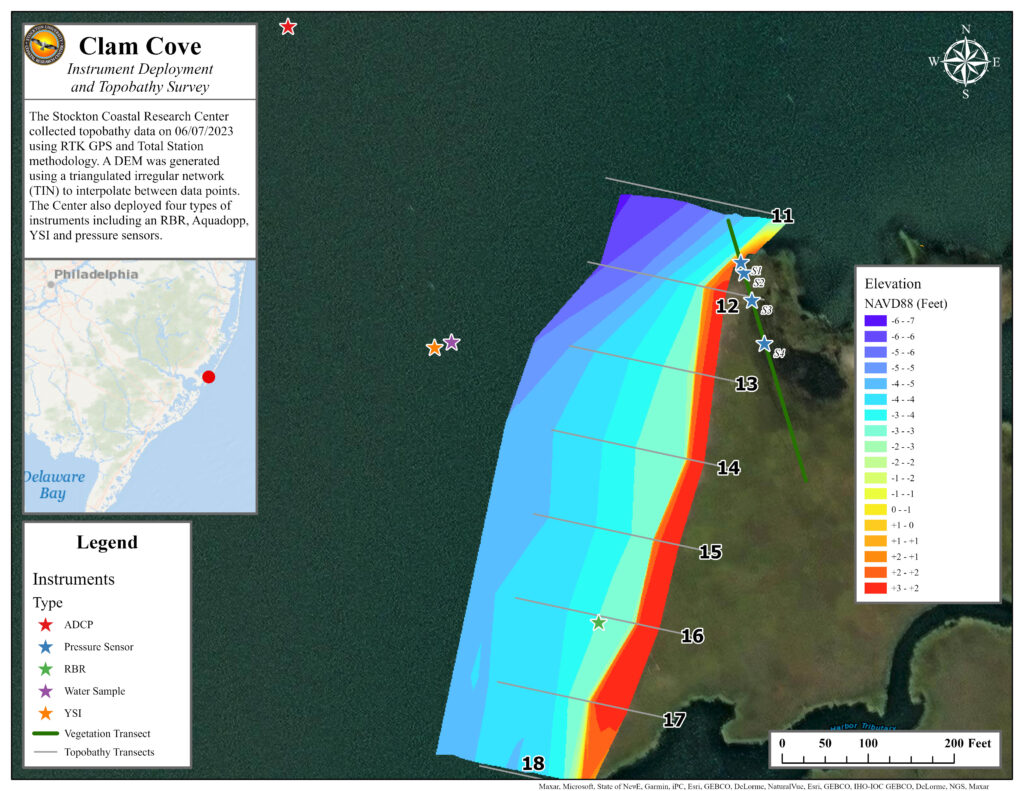

Ms. McKenna, CRC staff, and Stockton University coastal zone management graduate students installed instruments to measure waves and currents, turbidity, and water levels on Clam Cove. These data are compared to the meteorological information collected at the LBT Marine Field Station. The digital elevation model created from surveys of the marsh platform surface and nearby bay bottom (see digital model, left) shows a deeper bay bottom on the north side of Clam Cove and shallower areas to the south. Since elevations of Clam Cove range from 0.45 to 1.4 ft NAVD88, the (now) island is susceptible to flooding and increased edge erosion from storms.

Observing the erosion:

Andersen led the kayak and boat tour out to Clam Cove Island for everyone to observe the marsh edges. Clam Cove Island is disconnected from Clam Cove Reserve by a throughway that cuts the land in two, creating the island. The group paddled the throughway out to the “cove”, which is encompassed by a protective loop-shaped area of land. The opening where the cove meets the bay has widened exponentially, exposing the cove and leaving it vulnerable to further and continued erosive forces. The incessant wave action is causing cleavage of large chunks of marsh. The dissociated “muck” and its constituent salt grass (Spartina alterniflora) and ribbed mussels that hold the aggregation together eventually disintegrates into the bay. The island shrinks!

Additional factors indicated disparaging marsh edge health. For example, “marsh undercutting”, “terracing” and “calving” can all be observed. In some places, the substrate beneath the vegetative root mat was completely absent, leaving a “shelf” that will inevitably break-off and topple into the bay. Stark marsh grass size changes and the absence of ribbed mussels in some areas were also observed, which indicate prior erosion and attempted regrowth of the Spartina. These are focal areas for urgent assistance!

Combating the erosion – hope for the future!

Combining all the collected datasets will provide present-day conditions of Clam Cove and insights on the forces that are causing the erosion, and ultimately will lead to development of nature-based projects that are best suited for restoring the island. This valuable data collected by Ms. Andersen, Dr. Herrington, Ms. McKenna, and their students provides insight as to how the island may be be protected, preserved and/or restored. Possible short-term remedies may include installation of wave attenuation devices or similar oyster castle structures that would hold ground until a restoration plan can be finalized and permitted.

The NJBII group was formed in 2020 to address the lack of focus on the bay islands in Ocean and Atlantic counties, and to bring awareness to these often overlooked, yet undeniably important natural resources. NJBII partners include Long Beach Township, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Barnegat Bay Partnership, The Nature Conservancy, Stockton University’s Coastal Research Center, Monmouth University, the NJ Department of Transportation’s Office of Maritime Resources, and Ocean County Soil Conservation District, among many others. Over the past three years, the group has convened numerous online meetings to discuss and create resources designed to educate the public about why island restoration is key to ensuring resilience and stability within our communities and the natural habitats of the bay, and to provide tools to promote and support bay island restoration. NJBII partner, The Nature Conservancy, has developed an online tool called the NJ Bay Islands Restoration Planner (NJBIRP) which can be used by practitioners to plan island restoration projects from the Metedeconk River, south to Beach Haven / Little Egg Inlet.